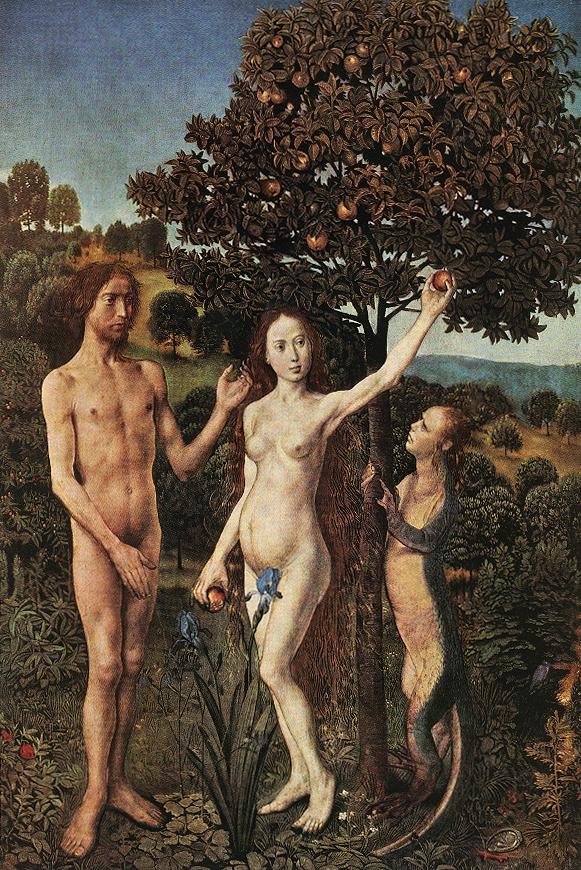

The Fall. Hugo van der Goes. Belgian, ca. 1440 - 1482.

I don't know who--or what--caused the shift. I don't know when it happened. I don't even remember consciously responding. But at some moment a tectonic shift took place and, ever since, I have had a radically different outlook.

As a product of this scientific culture, I prided myself on closely adhering to the standard of "Is it true?" when examining various aspects of human existence. True meant something demonstratively proven. Wishful thinking, speculation, and everything mysterious and miraculous, I labeled untrue or of questionable truth.

Of course, with that measure, much traditional religion was pushed to the periphery or simply discarded. How does one 'prove' the doctrine of the Trinity or the Biblical account of Jesus walking on water? Constructing a rational religion devoid of that which went contrary to reason was a decades-long successful effort.

A disturbing side of this paring away all not demonstrably proven resulted in a somewhat sterile religion--rational and reasonable, but devoid of that which captures one's imagination and fuels one's passion.

My tectonic shift--only recently recognized and articulated--subsumed the question, "Is it true?" to the question "How does it mean?" Rather than discounting or dismissing all non-demonstrable belief, I began to work from the premise that if something functioned in human belief and experience then it had to be taken seriously. I tried to determine the meaning of items as they relate to the human enterprise.

For example, the doctrine of original sin, stemming from Eve and Adam disobeying God in the Garden of Eden, was easily dismissed as a myth and an absurdity. But when I took seriously its persistence in Christian thought I asked, "How does it mean?" and found that it was an attempt to give some intellectual shape to a perennial human problem--the source and persistence of human evil. How do we understand the vicious destructiveness of humans (seen in the deaths of youth in Colorado or on the ground and from the air in Kosovo and Yugoslavia) or the less-than-pure motives of our own actions? Heredity and environment will explain this only so far. The doctrine of original sin (although not factually true) is functionally helpful in giving us a means to talk about the depth and persistence of human evil.

Perhaps the seeds of this personal tectonic shift came from living in Turkey. Instead of reacting to the habits and practices of the native Turks ("They don't do it the way we do it" [our way being, of course, the right way]), I began to ask how do their habits and practices function for them in the matrix of their society. Always, what was done (no matter how strange or non-sensical from my point of view) had meaning in their cultural context.

Of course, the filter of factuality has not disappeared.

It is alive and well. But beyond factuality, I have found a new

way to discover the life and vitality of an idea or belief by

also asking, "How does it mean?"

--Robert H. Tucker

19 April 1999