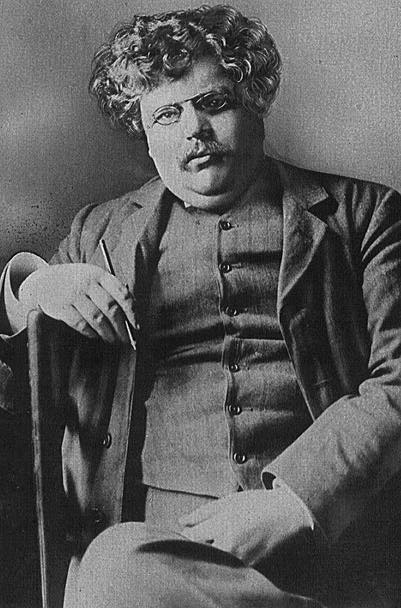

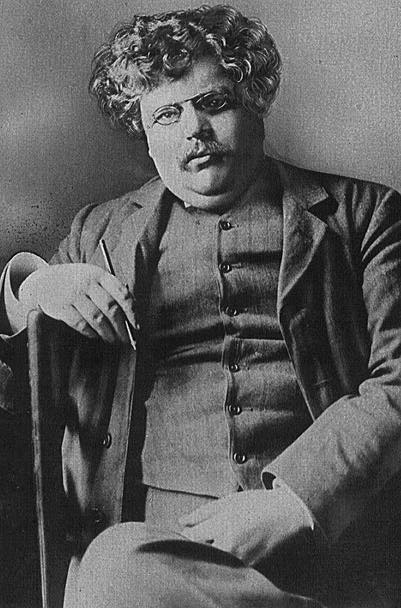

G. K. Chesterton (1874 - 1936)

The Earl of Chesterfield's "If a thing is worth doing, it is worth doing well" has accompanied many a child to school and into life. As a call to making the extra effort, perfecting the special project and striving toward the highest goal, much has been accomplished-far beyond many individuals' normal interest and diligence.

While true for some, for others this saying--translated into always doing one's best--has dogged their footsteps and blighted their lives.

A child comes home with straight "A's" and one "B." Parents' eyes immediately are glued on the "B" and an interrogation begins on the reasons for the 'failure.' A winning soccer team loses focus as the other team quickly scores two goals. The coach's voice rises, along with the opponent's score, and the tongue lashing lasts through the half.

Externally, the worth-doing-well-and-do-your-best stare at us in bookstores with book after book proclaiming how to cook, how to make a million, how to find real love and how to truly know God. A beaming face on the dust cover and simple descriptions and prescriptions on the pages reinforce our awareness of personal limitations and failures. These external reminders cling to our internal worth-doing-well-and-always-doing-one's-best measuring rod, and they take their toll.

The British writer G. K. Chesterton turned the Earl of Chesterfield around when he wrote: "If a thing is worth doing, it is worth doing badly."

I like that. Chesterton shifts the focus from doing something well to doing something worthwhile. Living by worth-doing-well-and-doing-one's-best, I would preach only once a month (twice a year would stretch it in some peoples' eyes). Living by "doing something worthwhile" frees me to preach weekly, even when I am not at my best.

Tracking that same thought is another of Chesterton's provocative aphorisms: the only cheerful doctrine is-original sin. Bending down, he pulls this doctrine out of the trashcan of twentieth-century Christian theology. It is a doctrine that allows us to be imperfect, indeed that tells us we cannot be perfect. If, as the Gospel states, God loves us even if we cannot be perfect, then it should be possible for us to love ourselves even though we aren't perfect. It might even free us from demanding perfection from others. Chesteron is right again. What a relief not to have to be perfect!

What a relief not to have to be perfect. We don't have to continually measure ourselves against the always-do-your-best-and-be-perfect standards.

So, the next time you see those smiling faces on the how-to-do-and-be-your-best

books, pass by with a smile on your own face. Chesterson's "the

only cheerful doctrine-original sin" will do it for you.

--Robert H. Tucker

22 March 1999